Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is calling for the introduction of a new, broader framework for the budget of the Ministry of Defense. The goal is to increase defense spending to the NATO recommended level of 2% of GDP over five years. The new head of the defense ministry, Yasukazu Hamada, is also presenting his ideas for increasing the military potential. As in Europe, the issue of air-raid shelters also returns to the public debate. It will come as no surprise to know that the situation in this area is also poor in Japan.

The draft budget for fiscal 2023, unveiled by the Japanese Ministry of Defense in late August, foresees spending of 5.596 trillion yen. However, this is not the final amount, the ministry is still estimating the costs of some projects. According to the media, this means that in the end, next year’s defense spending may reach 6 trillion yen, and thus exceed 1% of GDP.

For comparison: this year’s budget of the Japanese Ministry of Defense is 5.4 trillion yen. However, due to the record low rate of the yen against the dollar, the planned Japanese spending does not look so impressive after the conversion – it amounts to around $ 40 billion.

The increase in defense spending, postulated by Kishida and many politicians from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), has several catches that bite into creative accounting. The prime minister wants to adopt NATO standards not only on the level of measures relative to GDP, but also on the way of counting. Currently, the budget of the Japanese Ministry of Defense does not include expenses related to the coast guard, military pensions and UN missions. Taking these items into account, Japanese defense spending is not 5.4 trillion but 6.1 trillion yen, corresponding to 1.08% of GDP.

Exercises of the Japanese 7th (Panzer) Division.

(Rikujō Jieitai)

The daily Yomiuri Shimbun, which is critical of the government, also points to large fluctuations in the budget of the Japanese defense ministry. After taking into account the aforementioned pensions, coastguard missions and missions, as well as budget adjustments in 2021, defense spending reached 1.24% of GDP.

The basic question remains open all the time, i.e. where to get the money for it all? Remember that this is about 5-6 trillion yen a year. Yoichi Miyazawa, who is in charge of tax policy at the LDP, rejects the increase in state debt in advance. It is also reluctant to impose new public levies. Miyazawa wants to look elsewhere for the money in spending cuts, although he doesn’t go into details. He sees the increase in CIT as the main source of additional defense money.

Importantly, the idea of increasing defense spending is gaining increasing public support. In a survey commissioned by NHK public television in late September and early October, 55% of respondents were in favor of an increase in spending, against 29% against. The study was conducted on a representative group of 1,247 people.

Kishida, however, should be credited with the fact that his ideas include better coordination of the needs of the Self-Defense Forces (Jieitai) with scientific research and the improvement of the financing system of the latter. The National Security Council presented a plan to create a framework for an exchange of views with the Science, Technology and Innovation Council (CSTI), which distributes money for science and technology. The aim is, of course, to direct some of these funds to defense-related projects.

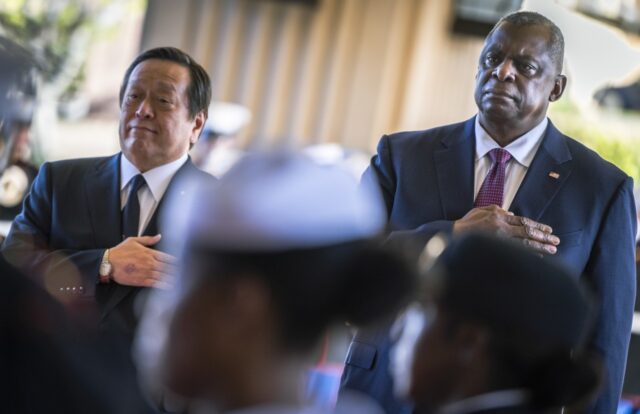

Japanese Defense Minister Yasukaz Hamada and US Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III.

(Chad J. McNeeley)

Meanwhile, CSTI’s Takahiro Ueyama, along with Kazuhito Hashimoto, president of the Japan Science and Technology Agency, proposed the creation of non-university research centers to expand scientific and technological research in military-related fields. This is in line with the prime minister’s idea to create the Japanese equivalent of the American DARPA agency. In recent years, similar concepts have also appeared in China and Germany, but their implementation is extremely slow, not to say at all.

Awaiting 2027

The year 2027 is often mentioned by US officials and analysts as the date when China achieved the capacity to conduct an effective military operation against Taiwan. Regardless of the validity and probability of these assumptions, 2027 is a convenient date for military planners. Japanese plans for the five-year plan can be summarized as: increasing the range of means of destruction, development of hypersonic missiles, anti-aircraft and anti-missile defense, implementation of combat drones.

The development of these specific capabilities is expected to allow Jieitai to successfully repel any Chinese attack on Japanese territory. It is primarily about the disputed Senkaku archipelago, called by the Chinese Diaoyu. On the other hand, in the field of drones, Turkey is airing the chances for good business. The war in Ukraine turned out to be a promotional campaign by Bayraktars TB2. Already in March, Baykar opened its drones to Japan. The offer was officially sanctioned in September, when Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu was in Tokyo. He confirmed that Ankara is interested in selling Japan unmanned aerial vehicles of various types, not only Bayraktars.

Yasukazu Hamad, who replaced Nobuo Kishi as Defense Minister in August, presented the government’s expert panel on October 20 with a ten-year plan to increase the combat capabilities of the Self-Defense Forces. The first stage covers the period until 2027. During this period, the process of acquiring combat drones is to begin. The purchases are to start next year. However, in the budget year 2026, a development version of the type 12 anti-ship missile is to be introduced into service, with a range increased from 200 kilometers to 900 kilometers, which will allow the enemy, i.e. China, to be hit beyond the range of its anti-aircraft defense. The second five-year plan is to include the implementation of hypersonic missiles and swarms of unmanned aerial vehicles.

Launch of a type 12 anti-ship missile from a land launcher.

(Ministry of Defense of Japan)

Shelters and more

So many plans. Japan’s defense ministry has to deal with other, more pressing issues. In a surprising move, the ministry admitted that the warehouses contain only 60% of the anti-aircraft and anti-missile missiles necessary to defend the country in the event of a war with China or North Korea.

Another issue is securing the population against the possibility of a missile attack. The situation looks bleak here. Over the years, Japanese services and civil defense have specialized in disaster relief. As a result, the effectiveness of Japanese civil defense in the event of war is questionable. The government of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe tried to remedy this and conducted a series of anti-missile exercises in 2017–2018. However, for not entirely clear reasons, they were suspended after Donald Trump’s meeting with Kim Jong Un in Singapore in June 2018 and have not been resumed.

Now the case is back. Russian attacks on Ukrainian cities and the flight of North Korean ballistic missiles over northern Japan have made the shelters a media topic. It turned out that as of April 2021, there are 51,994 facilities throughout the country where the population can shelter from an air or missile attack for one to two hours.

However, the bunker is unequal. The classic European definition of a shelter, i.e. an underground structure with reinforced walls and ceilings, is filled by only 1,278 structures. One tenth of this is in Tokyo. Aomori Prefecture and Hokkaido, over which North Korean rockets flew on October 4, have only eight and sixteen underground shelters respectively.

The equipment of the facilities is a separate issue. In addition to access to water, energy and medicines, the issues of adapting shelters to the needs of the elderly, disabled and children are discussed. The authorities also admitted that in many bunkers it was necessary to replace the door with a stronger one, able to withstand the blast of a nearby explosion.

Various remedial measures are taken into account. The obvious use of metro stations as bunkers in Europe is in the foreground. Another option is a permit to build private facilities. The Japanese media put Switzerland, Israel and Singapore as a model, where the shelters can accommodate from 90% to 100% of the population. For the much more populous Japan, however, this is a very high bar, especially in the current state of affairs.

American and Japanese soldiers during Orient Shield 14 exercises.

(US Army)

Kishida’s government honestly informs that building an adequate number of shelters is a project for many years. The Cabinet Secretariat, roughly the equivalent of the Prime Minister’s office, demanded 70 million yen (nearly half a million dollars) for analytical and conceptual work in next year’s budget. To begin with, new shelters are to be built in Okinawa Prefecture, closest to Taiwan. There are only six shelters in the entire prefecture, all in Okinawa. In order to speed up the works, the construction of ground shelters is being considered.

Local authorities react faster than central authorities, but they have limited possibilities of action. Local government officials from the islands of Ishigaki and Yonaguni, located just over a hundred kilometers from Taiwan, asked the prefectural authorities to build shelters in July. Just erecting facilities is only half the story. Professor Naofumi Miyasaka from the National Defense University draws attention to the need to resume civil defense exercises in the field of air and missile attacks.

See also: First American lessons from the war in Ukraine

Rikujojieitai Boueisho