Throughout history, the sparks that ignite revolutions are unpredictable. They all have something underlying: discontent caused by a crisis – social, political or economic –, so deep that it leads people to confront the authorities and their fears, demanding changes in the dynamics between power, elites and the people.

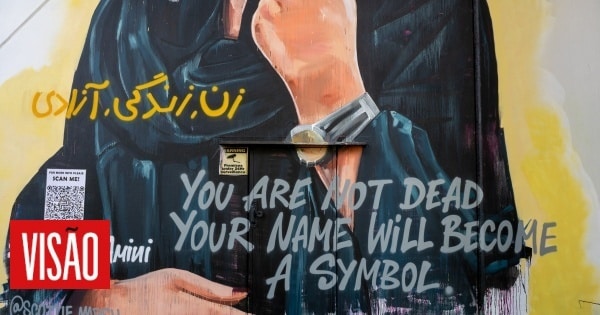

In the case of Iran, the spark of the revolution has a woman’s name: Mahsa Amini, the young Iranian woman killed at the hands of the customs police. And a slogan: “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” – Woman, Life, Freedom. These are the watchwords since September in Iran: the chant first used by women activists and Kurdish fighters in the late 20th century and now adopted by women and men of various ethnicities when challenging a violent and authoritarian patriarchy, removing their hijabs and demanding fundamental rights and an end to the regime.

Iran has been plagued by other clashes in the past. In 2009, the Green Movement protested for months against the fraudulent presidential election results. Ten years later, the country again experienced a series of riots, caused by a rise in fuel prices, quickly repressed with violence. It is estimated that around 1,500 people were killed in one week. This time, the protests, which have already lasted two months, extended to the whole country, with at least 155 cities involved. According to the calculations of local humanitarian organizations, 17 thousand demonstrators were arrested and more than 400 died.

What distinguishes these protests from previous ones is not just the scale but the essence of the discontent and the form it takes. There is a fundamental point: this revolt is led by women. And this is not a detail.

According to Erica Chenoweth, an expert on the history of civil resistance, masses, and political repression, cited by Politico, movements in which women participate in large numbers are statistically more likely to be successful and to trigger more periods of sustained democratization. This is the conclusion of a study she conducted with Zoe Marks, professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. And movements with large numbers of female participants tend to be perceived as more legitimate in the eyes of observers, who often respond to the symbolic power of protesting grandmothers and schoolgirls.

Iranian women are on the streets and show no intention of giving up. And they are with them.

A few days ago, in Qatar, the players of the Iranian national team, led by Carlos Queiroz, took on an act of rebellion broadcast live around the world: they remained in the deepest silence during the national anthem. And the captain of the team, Ehsan Hajsafi, assumed later, in the press conference, that his people “are not happy”.

Last week, videos were released showing a crowd burning down the house-museum of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution, which overthrew the shah and installed a repressive regime. It is a symbolic milestone: the people lost their fear of the ayatollahs. And he begins to call for “death to the dictator”, a cry directed at the current supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, Khomeini’s successor.

In the meantime, Iran is managing discontent while getting closer to Russia and China, and evading the economic sanctions imposed by Europe and the United States of America through a well-built clandestine financial network, full of ramifications.

It’s just that, while there is broad national sympathy for the protests, a key element is missing for the time being, which was decisive in 1979 to overthrow the monarchy: strikes. As the Financial Times noted a few days ago, the majority of Iranians are not joining the strikes, which are essentially inorganic and disorganized, because they fear losing their jobs. Workers in crucial sectors such as oil, gas and petrochemicals have not yet gone on strike. And, without that, it is very difficult for the regime to be shaken in its structure.

May these brave women and the men who join them have the strength and courage to continue the fight.

MORE ARTICLES BY THIS AUTHOR

+ How not to carry out a constitutional review

+ Raimundo, the worker (of politics) that follows

+ The dangers of the Brazilian limbo